It's a Bird! It's a Plane! Its a Printer Paper Airplane?: Questioning the Value and Process of Paper Airplane Craftsmanship

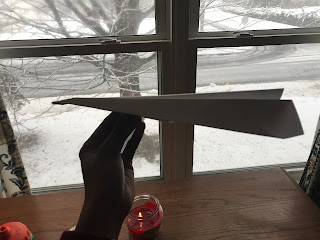

It honestly took me three attempts to craft a plane like the plane within the directions. To craft my paper airplane, or should I say paper airplanes, I used blank sheets of printer paper. The first step that I took was to fold the paper in half (I folded it so that the plane’s width would have a horizontal length over 9 inches). The next step that I took was to flip the paper over and to take a corner of my folded rectangle and to fold this corner over, making a small triangle over top of the original rectangle fold. Next, I took the corner opposite of the triangular fold and made the same triangle shape as I folded this corner over the rectangle base. To follow these steps, I started to structure the wings of my paper aircraft. My first step to make the wings was to fold the paper again in half so that I could only see one side of the plane. Then, I proceeded to take the side facing me and made another fold of the entire horizonal slit of the plane. I then turned the plane to the opposite side and repeated this on the side that had not yet been folded. The plane flies well, if I do say so myself!

If I came across this

airplane as a historical artifact, I would ask questions like: Who made this

plane? Why would someone make an airplane using printer paper? Did they have

any other resources on hand to make an airplane, yet they chose printer paper? Since

I made three attempts to fold together a paper airplane, I might even ask how much

time it took to craft said plane. I would say that questioning what resources

were available to the airplane craftsmen/craftswoman is important, in that by

asking this question, a historian might be able to answer what material the

person valued, or thought was ideal to take on this task. Likewise, the maker

of the plane may have used the printer paper to make the plane not for a

perceived high value of printer paper, but because they themselves or the

society they lived in thought that this was a form of paper or crafting resources

that was the least valued. Some artifacts are made from items that people

usually dispose of, so it would be important to not assume right away that an

artifact was crafted from the most valued resources. For example, I am a

proponent of recycled materials, and though some people dispose of newspapers,

water bottles, and other recycle materials in a means to be rid of them for

good, I have owned a pencil, a bag, a notebook, and other items which were made

from recycled materials.

Comments

Post a Comment